One of the most popular indigenous genres of music in Nigeria is fuji music. Fuji music began as a socio-cultural movement in the South-West region of Nigeria in the early 60s, when Nigeria had just gained its independence, and has since travelled beyond its borders. Primarily known for its percussive and up-tempo style, fuji saw its popularity rise with Owambe parties, powering dance floors all over metropolises from Lagos to Ibadan. Fuji evolved from “were” music, an improvisational style similar to a Muezzin’s call to prayer, which was performed in the ‘50s to keep Yoruba Muslims entertained in the wee hours of the morning during the holy month of Ramadan. The uptempo beat ensured they didn’t fall asleep before eating Sahur (a meal consumed before dawn). For those who were asleep, were music roused them from their slumber in time for Sahur.

“Were” (pronounced as wayray) music, also known as “ajisari” or “ajiwere”, was invented and popularised by musicians like Alhaji Dauda Epo-Akara (also recognised as the founder of awurebe music) and Ganiyu Kuti (aka Gani Irefin) in Ibadan. The music was performed in groups by ajiwere singers who paraded the streets in the middle of the night and sang with unrestrained enthusiasm. As were music became popular between the ‘50s and ‘60s, various were groups sprang up in different cities across western states of Nigeria. In the boroughs of Lagos, specifically in Isale Eko (Lagos Island), Mushin and Oyingbo, ajiwere groups were being formed such as Jibowu Barrister and Band, Sikiru Olawoyin and Band, each group having its distinct style of music and performance. These groups adopted the use of local instruments such as the sekere, agogo, sakara and bembe to invigorate their singing. One of the factors that sparked the popularity of were music in the ’50s was seasonal competitions held during the month of Ramadan as were was only performed during Ramadan. It was from these competitions that Alhaji Sikiru Ayinde Barrister emerged, gaining notoriety for his prodigious singing talent. He won many of these competitions with ease, and in no time, different were groups proposed that he join them as lead singer. Alhaji Sikiru Ayinde Barrister’s new were style caught the attention of music lovers as he infused his lyrics with Quranic recitations, which appealed to the majority Islamic audience. He was also the first were performer that employed the use of the harmonica (commonly known as the mouth organ) and flute in his music. It was his idiosyncratic approach to were that led to the birth of fuji.

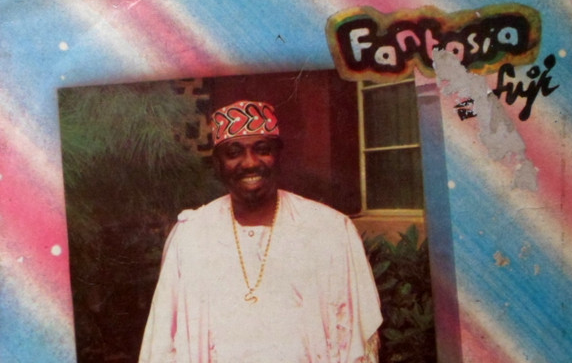

Ayinde Barrister is said to have come up with the name “fuji” after he saw a poster advertising the popular Japanese tourist attraction, Mount Fuji. It was while working between a range of jobs from a typist to a clerk in the military that Sikiru Ayinde Barrister had his eureka moment. He decided to create a this new genre, fuji, so he could continue to perform music outside of the Ramadan season. His plan worked. Within a few years, Barrister’s records were heavily rotated on the streets and in the homes of music listeners. He soon became a household name and gained a reputation for his brilliant use of poetic Yoruba lines to craft lyrics on life, wealth, women, death, politics, and poverty. On records like Fantasia Fuji, he croons, “Bi’ku se lagbara to ko so’loogun to le ri ti’ku se,” which translates to “Death is so mysterious and powerful that no shaman can provide any charm to prevent it.” He became especially famous in the ‘70s and ‘80s, releasing a handful of studio albums and recordings of live shows and toured America and Europe where fuji music had just begun to receive global attention. Towards the late ‘80s, Ayinde Barrister also began to blend early elements of hip hop with fuji – using hip hop flows and rhythm – after he returned from his international tour.

The ‘70s and ‘80s also brought with it the rise of other fuji musicians such as Fatai Adio, Waidi Akangbe, Iyanda Sawaba, Rahimi Ayinde, Love Azeez, Agbada Owo. However, only one name compared to that of Ayinde Barrister, and that was Alhaji Ayinla Kollington (popularly referred to as Kebe n’ Kwara). Emerging around the same time that Barrister created fuji, Ayinla Kollington introduced his peculiar style of fuji that rocked social circles. His style of fuji was groovy and his command of the Yoruba language beguiled listeners. As the ‘80s wound to an end, a rivalry broke out between Ayinde Barrister and Ayinla Kollington. The two rivals, who started off as childhood friends, formed separate alliances that pitted them against one another as they chased their individual careers. They were at each other’s throats for years, throwing shots at each other in their music, including in albums like Ijo Yoyo, Fuji Garbage and Lakukulala. This rivalry birthed a fanaticism where fans of both acts were forced to take sides, sometimes clashing at shows, and causing an uproar that was often uncontrollable.

This fanaticism created the building blocks for fuji music as it brought more attention to the genre in the mainstream. The rivalry between both leading fuji acts boosted record sales as fans would impatiently analyse the latest lyrics. The popularity of fuji surged in those years and the local shows that both Barrister and Kollington played swarmed with fans who would go to any length to defend their idols. This inspired a new wave of fuji performers in the ‘80s and ‘90s who yearned to show their God-given talent.